Nonlinear control is rarely applied in outside of an academic setting. Industry implementation of control algorithms most often focuses on linear classical theory even for highly complex systems. When a nonlinear control strategy is implemented in an industrial setting, often times it performs worse than the simple linear controller.

In some sense this is a paradox: one would think a plant model and associated control architecture more reflective of the true system dynamics would lead to a better performing controller. After all, how many systems in the natural world are truly linear? Hardly any. It turns out the opposite is true: these sophisticated nonlinear controller implementations often perform poorly compared to simple linear theory in the vast majority of circumstances. The reason is due to what I call “The Paradox of Information” in control theory.

Ill summarize the paradox here: While linear systems often do not reflect the true physical nature of a system, nonlinear controller implementations may require either more system parameter information, more accurate system parameter information, or both; nonlinear controllers are often more sensitive to these uncertainties or errors, even though the structure of the under laying equations are more sophisticated and better reflect the nature of the dynamics.

For the more seasoned control theorist: nonlinear controllers are often not robust controllers.

Let me illustrate a simple example.

Imagine we want to control the movement of a block on a surface. We have access to both position and velocity information, and a control force is applied to achieve movement. The system dynamics in scalar form are,

To account for friction, often a simple linear dissipation is added to the dynamics; often a reasonable assumption for most applications, especially at slow speeds or when working with newtonian fluids.

However, anyone who has taken a first level physics course knows this does not take into account the initial force required to move the block from rest. In high school or early undergraduate classes this is called static friction, but at higher levels is referred to as stiction, which encompasses the more detailed physics of this phenomena. In the event that one wishes to design a controller that allows the system to have better transient response performance (during start up or stopping), one may need to take stiction into account.

The most simple way to do this is to assume there is a stiction force that fully opposes the control force until some threshold is met, at which time the linear damping term takes over.

when

, otherwise

However, some people might be interested in a more detailed description of the physics an mathematics, even if it has no real practical benefit (people like me!).

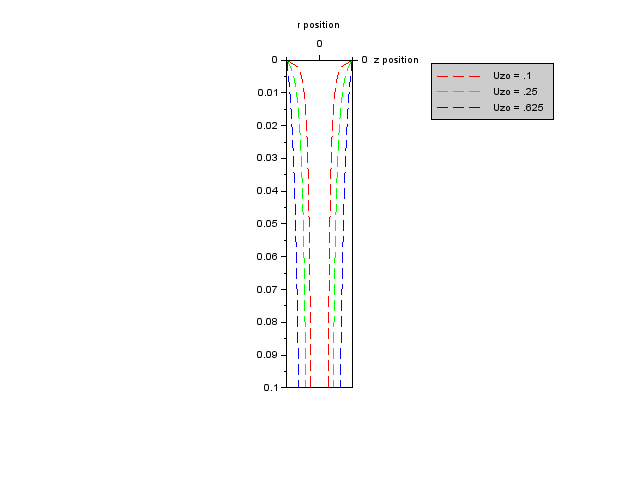

Lets assume the stiction force is a function of velocity and has qualitative behavior as follows: when the motion is 0, the stiction force is 0, however during start up when the velocity of the block is slowest the force reaches a maximum, followed by a rapid decline to zero where the linear term begins to dominate the dynamics. The force must always oppose the direction of motion. There are many functions which meet these criteria, one of which is:

Which introduces parameters A, B, C into the system. It is easy to see that changing each of these parameters results in very different friction behaviour. It is most intuitive to look at this graphically, but one can also take the variation of the stiction force with respect to each of these terms to see how the force changes with changes in the value of these parameters.

The new system dynamics become

or

where

for

and 0 otherwise. The more sophisticated model requires knowledge of 3 parameters, and the simple model requires knowledge of 1 parameter only. These parameters will depend on the characteristics of the sliding surface and the surface of the block, along with other environmental factors that may not easily be predicted, such as the cleanliness of the surfaces. In fact, cleanliness is one key reason why natural laminar flow airfoils (wing sections with very low drag properties) were found to be impractical to use on aircraft.

The first model may opt to use a sophisticated Lyapunov approach to controller design, the second could simply employ a PID control law with an additional feed forward term to account for the initial nonlinear characteristics of the dynamics.

Even if the Lyapunov approach proved to be easier to implement than expected, there is still an issue of ascertaining the value of these parameters. For the simple model, one can simply lay the block on a ramp who’s angle is increased until the block begins to move. This will give a very good first approximation of the friction coefficient. The more complicated model will require a complete test set up, with access to instruments that can precisely measure velocity and force, followed by data processing to fit our empirically obtained curves to the selected stiction model. In both cases these tests will have to be repeated to capture the expected operating environments.

This example illustrates the additional “baggage” associated with more sophisticated models and control strategies. In an academic setting I might take the time to write a more detailed mathematical description of the paradox, followed by a recommendation for researchers to focus on robust nonlinear control, as it has the unique benefit of being both theoretically challenging and practically useful.

For now, the best resolution to the paradox of information in control theory is to stick with classical controller designs as often as possible, coupled with a thorough understanding of the operating environments to which the classical theory applies. The solution I would like to see, and maybe will pursue myself in the future when the time is right, is more research into robust nonlinear control.